This is How to Japanese, a monthly newsletter with something about Japan/Japanese and a dash of いろいろ.

日本・日本語: 死亡確認

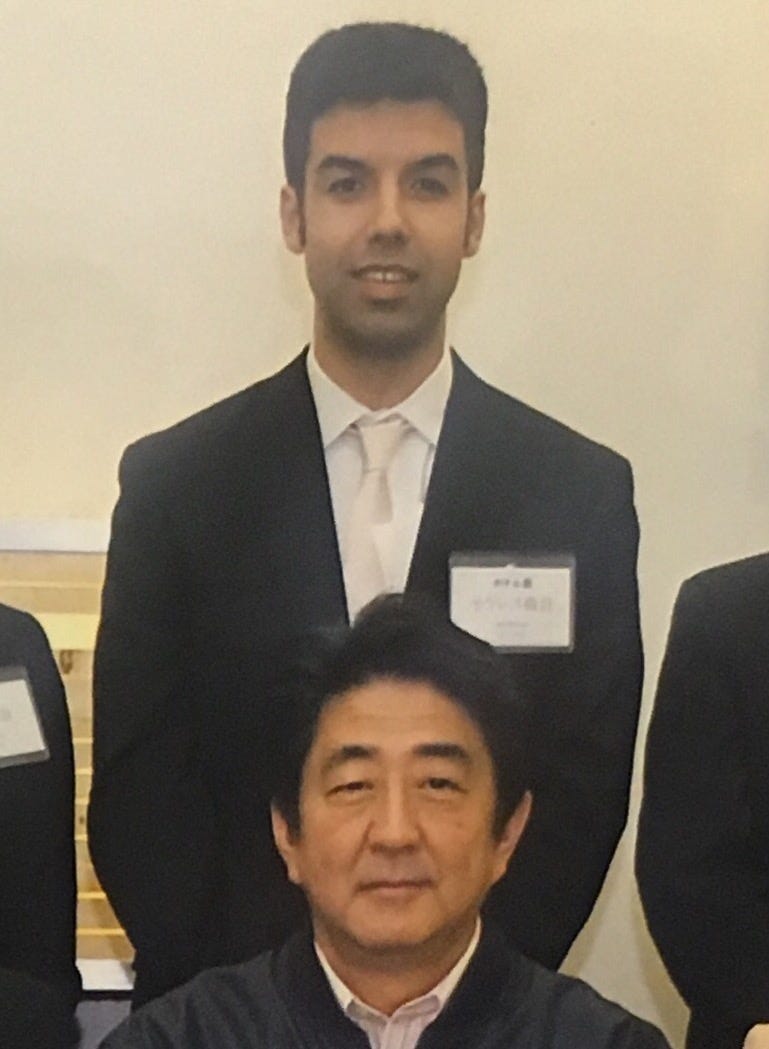

In August 2014, I was working at the Consulate-General of Japan in Chicago when then Prime Minister Shinzo Abe had a four-hour layover at O’Hare International Airport on the way home from Brazil. The Consul-General and other MOFA officers regularly stopped by O’Hare to attend to politicians and diplomats on layovers, but it was the first time I was asked to staff anything remotely similar.

The visit came on almost exactly the one-year anniversary of my time at the consulate, so I was familiar with the typical breathless, panicked preparation for consulate events that ultimately went off without much of a hitch. In my experience, this visit was the same.

We all got picked up by consulate drivers at around 10:00 or 11:00 at night and prepped the airport and hotel. At some point in the early hours of the morning, Abe and his team arrived, escorted by Secret Service members who flowed into the hotel in the loosely fitted black suits you see on TV. I had positioned myself along the hotel hallway for his arrival and stood there and bowed as he walked by. It felt very unreal. I was also very tired.

After that point I was basically a non-factor. I staffed the room for the press corps on the ground floor of the hotel, and I remember doing very little. At one point I escorted a few members of the press to rooms on the upper floors where they were allowed to use the showers. My main contribution came the next morning, after Abe had departed for Japan, when I suggested we should start cleaning up so we could leave soon.

The most memorable moment of the visit was the photo opportunity with Abe. I don’t remember the circumstances of how it happened, but those of us staffing the hotel were called to take pictures with him in several groups at around 5:00 in the morning. I was suddenly whisked into a room and found myself standing behind the Prime Minister. I was exhausted and worried it would show on my face. Months later I was given a small six-inch by eight-inch glossy photograph with a raised seal, which I’ve since framed as a memento. I managed a decent smile.

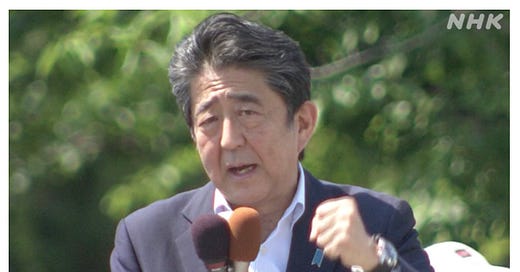

So it came as a shock to hear that Abe had been shot on July 8, late in the evening on July 7 here. I’ve been back in the U.S. since July 2 and was jet lagged and disoriented as I moved out of my apartment in Chicago. I was out with friends that night and only saw the news upon returning home. For anyone familiar with Japanese news reporting, it was almost immediately evident that Abe was dead even if they weren’t saying it. The most critical phrase was missing: 命に別状はない (inochi ni betsujō wa nai, not life threatening). This is the phrase used consistently across news stations when an accident or incident happens and people have been injured but their lives are not in danger. There was also the ominous 心臓停止 (shinzō teishi, heart failure). However, there wasn’t the usual phrase of confirmation—死亡が確認されました (shibō ga kakunin saremashita, the death has been confirmed)—for several hours.

死亡確認 (shibō kakunin, confirmation of death) is a serious matter in Japan and can only be performed by doctors and dentists. This is the reason news reports often have a delay from the start of an incident/accident to the reporting on the number of deaths. This is wrapped up with a generally tentative approach to reporting. With Abe’s shooting, this phenomenon is best exemplified by the phrase 血のようなもの (chi no yō na mono, something resembling blood) which was used in the immediate aftermath as bystanders attempted to revive Abe. Because Abe was giving a political speech, his killing was basically captured live in front of reporters who could see the blood on his shirt from where they were standing. Yet they were unable to call it like they saw it. Even Japanese were a little frustrated by this noncommittal description of something so obvious.

(Translation of tweet: “I’ve heard this phrase ‘something resembling blood’ on the news over and over. So they’re basically saying it this way because they can’t deny the possibility that Abe-san might have had ketchup in his shirt pocket?”)

This phenomenon is not wholly limited to journalism. This article has a really close look at how 死亡確認 take place in the medical field in Japan. It’s worth reading the whole article to understand exactly how much consideration goes into this process and the ramifications of getting it wrong. (I was surprised the writer admitted how much theater goes into the process.) This must have been especially true in Abe’s case. I imagine the doctors tried everything possible to save him and only made the call at the last possible moment.

From the article, these are the three steps that go into a confirmation of death:

死亡確認の実際と注意点

実際の死亡確認では、

◎ 胸部の聴診で呼吸と心拍が停止していること

◎ 視診で頸動脈の拍動が停止していること

◎ ペンライトで対光反射が消失していること

を確認するのが、最低限の手順です。頸動脈や橈骨動脈の触診をする場合もあります。

Precautions for making a confirmation of death

In an actual confirmation of death, you should:

- Use a stethoscope on the chest to confirm the patient is not breathing and has no heartbeat

- Visually confirm that the pulse in the carotid artery has stopped

- Use a penlight to confirm the patient has lost pupillary light reflexes

These are the minimum steps to be taken. There are also cases when you should palpate the carotid artery and radial artery.

Really a fascinating article. Not all that different from this explanation in English, although the English version has a lot less consideration for family members. The two notable absences from the Japanese confirmation are response to pain and exposure (body temperature), although I imagine a Japanese confirmation would take into account circumstances (i.e. a death in the middle of the woods would be treated differently than a patient being resuscitated on an operating table).

Over at the Japan Times, Tadasu Takahashi has a great rundown of the language used in reporting on the assassination. This is an article that I wish I’d been in a position to write, although being back in the U.S., I didn’t have that immersion that would have been really helpful. His context on the absence of the term 暗殺 (ansatsu, assassination) is particularly interesting and not something that I was aware of. Absolutely worth a read. Matt Alt and Patrick Macias have also discussed the incident on their podcast, which has been a great listen.

NHK, my main source for the news right now, is going with variations on this mouthful: 安倍元総理大臣が奈良市で演説中に銃で撃たれ死亡した事件 (Abe Moto-Sōri Daijin ga Nara-shi de enzetsu-chū de utare shibō shita jiken, the incident in which former Prime Minister Abe was shot and died during a speech in Nara). This choice reflects the care that’s going into reporting, especially now that the killer’s motives and connections with the Unification Church have been widely revealed.

Abe’s death does not seem to be a 9/11 moment for Japan. I’m sure there will be more of a ripple effect than whatever was the response to the 2007 assassination of the mayor of Nagasaki, but even Abe’s state funeral has been controversial; I recommend this Mainichi editorial, which is far more skeptical than I would have guessed.

いろいろ

Required reading to understand the Unification Church. This article came out last year, but I’m still surprised it wasn’t shared more widely in the immediate aftermath.

If you are looking to follow a single thread about Abe’s killing, this is the one I’d recommend.

More reports about the assassin's motivations, with more vague wording about a "certain group" (特定の団体) that he hated and associated with Abe. This is even more vague than earlier reports that suggested it was a religious group. 1/NHK: "He had a grudge against a certain organization and believed that Abe had connections to it, which led him to commit the crime." "his mother became involved in the organization and donated a large amount of money to it, which ruined his family life. https://t.co/ETaG0lw1UH

More reports about the assassin's motivations, with more vague wording about a "certain group" (特定の団体) that he hated and associated with Abe. This is even more vague than earlier reports that suggested it was a religious group. 1/NHK: "He had a grudge against a certain organization and believed that Abe had connections to it, which led him to commit the crime." "his mother became involved in the organization and donated a large amount of money to it, which ruined his family life. https://t.co/ETaG0lw1UH みつを_Mitsuwo🌻 @ura5ch3wo

みつを_Mitsuwo🌻 @ura5ch3woThis looks amazing.

In other Taro-related news, three of his early works were discovered in France.

I was in the Japan Times late last month with a look at the Japanese translation of Seinfeld. I have some outtakes over on the blog, including one mistake I found in an exchange between George’s parents.

I'd rather translate 心臓停止 as "no vital signs". This would be the situation if someone was pulled out of a river, but maybe still could be resuscitated. "Heart failure" has a technical meaning different from this.