This is How to Japanese, a monthly newsletter with something about Japan/Japanese and a dash of いろいろ.

日本・日本語: 街

I can vaguely remember my first encounter with 街と、その不確かな壁 (Machi to sono futashika na kabe, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall).

I was a senior in college and had only just gotten to the point where I could read Japanese confidently on my own. I’d gotten interested in a collection of Murakami Haruki’s short stories titled 回転木馬のデッド・ヒート (Kaiten mokuba no deddo hīto, Dead Heat on a Merry-go-round), so I started digging around for topics to write about. Murakami initially serialized the collection in the magazine IN POCKET as a favor for an editor, and the first story appeared in the inaugural issue in October 1983 under the collective heading 街の眺め (Machi no nagame, Views of the City). That got me thinking about 街 (machi, town/city) in Murakami’s work.

For his first few novels, 街 is a driving force. In Hear the Wing Sing, his Boku narrator is back in the unnamed town, which is clearly supposed to be somewhere outside of Kobe. He drinks beer with his friend the Rat, takes care of a girl who passes out drunk in the local watering hole, and seems to be trying to come to terms with the suicide of a girl he dated. In Pinball, 1973, Boku has escaped to Tokyo, but the Rat remains in the town and starts to feel the march of time metaphorically but also literally as Japan’s rapid growth erases the town’s beaches and throws up tall buildings. In A Wild Sheep Chase, Boku makes a day trip to the town to do a favor for the Rat and finds he no longer feels bound by his connections to the town as he once did. He’s been freed.

For his next novel, Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, Murakami took the concept of machi to an extreme and turned it into an abstract entity—“the Town” in English translation (emphasis my own)—surrounded by a wall and ruled by a brutal Gatekeeper who shepherds flocks of golden unicorns in and out their pasture each day. The citizens of this crumbling and vaguely European town are anonymous and spiritless, having been separated from their shadows. The Boku narrator tries to fit in as the Dreamreader and gradually learns that he’s connected to everything and everyone there.

As I began to go through Murakami’s bibliography to make sure I wasn’t missing anything, I was surprised to see machi at the front of a 1980 story I hadn’t heard of before. I found a copy in the September 1980 issue of the literary magazine Bungakukai, and when I started reading “Machi to sono futashika na kabe,” it started to feel more and more familiar. There were the Town and its wall. There were the Gatekeeper and the Librarian. There were the bridges and rivers and the flocks of unicorn. And there was the narrator, reading old dreams in the library. This was basically the “End of the World” sections of Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. What was going on here?

The story—a novella, really; it’s longer than most Murakami short stories—was only vaguely connected to my eventual thesis topic, so I didn’t have time to find out unfortunately. I set it aside in 2005 and didn’t pick it up again until 2009 when I did a translation as a personal project. I made a few edits in 2011 and analyzed passages on my website over the years, but other than that, didn’t really think too much about it.

That is until yesterday when Shinchosha announced that Murakami’s next novel, coming out on April 13, will have the exact same title as this 1980 novella.

Or will it? The first thing that that stands out to me is the lack of a comma. The novella is 街と、その不確かな壁, while the novel will be 街とその不確かな壁 . It’s much cleaner without the comma.

We have a short description of the book from the Shinchosha website that suggests that this will indeed take place in the same world as Hard-boiled Wonderland…or at least half of that novel. Here’s my rough translation, in which I’ll continue to use “town”:

I have to go back to the Town, no matter the cost. A story that’s been sealed away begins to move quietly from the depths, like the old dreams that unraveled and awakened in the hidden away library. This is a 100% Murakami world that will shake your soul.

その街に行かなくてはならない。なにがあろうと――〈古い夢〉が奥まった書庫でひもとかれ、呼び覚まされるように、封印された“物語”が深く静かに動きだす。魂を揺さぶる純度100パーセントの村上ワールド。

The next thing that stands out is the English subtitle provided on the Japanese cover. Gone is Alfred Birnbaum and Elmer Luke’s “Town” in favor of “City.” This shocked me, but I can of understand it. Murakami himself has used the word in a more urban sense in the past: The stories in Machi no nagame basically relate people living their lives in Tokyo as they’re pulled around by various fates, compulsions, and coincidences. It would be sad to lose that atmosphere of “the Town,” so I’ll be curious to see whether the eventual translator keeps it. And if they don’t, does that mean something about the machi has changed?

We also have “Walls” plural in place of “Wall” singular. This didn’t surprise me quite as much. I could see it working well in translation. But it’s an interesting choice.

That’s all we know about the new novel so far. I know a good bit more about the novella, so I thought this month, I’d do an FAQ and go over everything I know about that novella and what it might imply for the new novel. **SPOILER WARNING** I’ll be talking extensively about Hard-boiled Wonderland and this novella.

What’s the deal with this novella Machi to, sono futashika na kabe? Why haven’t I ever heard about it?

You haven’t heard about it because Murakami has never republished the novella in a collection or in his Complete Works. In supplementary text included in his 1991 Complete Works, Murakami calls it a “failed work.” In a 1991 interview in Bungakukai, he adds that in 1980 he was up for the Akutagawa Prize for Pinball, 1973, and someone suggested he should write something, I think ostensibly as a follow-up if he won the award. Murakami says he didn’t have the skills to write the kind of story that he tried to write and that he regrets writing it. The only way to read the novella is to go to the library in Japan and print a copy from the September 1980 issue of Bungakukai.

What’s the novella about?

It’s basically the End of the World sections of Hard-boiled Wonderland wrapped in an experimental shell. The narrator goes to an unnamed Town which is run by the Gatekeeper and inhabited by beasts and spiritless people who have their shadows cut from them. He reads old dreams in the library. He’s friends with an old colonel who’s a resident in the same quarters. He tries to tease out the mysteries of the town as his shadow grows sicker and sicker helping the Gatekeeper burn bodies of dead beasts.

How does the novella differ from Hard-boiled Wonderland?

It has an experimental intro and ending, and it’s narrated in second person. The narrator is addressing “you,” a young woman he knew outside of the Town. She tells him about the Town where her real self lives and the Town gradually takes form. If he wants it enough, she says, he can go there, too. And he eventually does, but when he arrives she doesn’t recognize him. Her shadow died in the Town, and he realizes he only truly loved her shadow.

Other than the second person narration, there are some sections at the beginning and end about how “words are meaningless” and how words “reek of death, rotting.” The narrator talks about how much he’s lost, how he’s surviving. It’s not fleshed out and doesn’t connect well with the rest of the story. Once Murakami gets into the core of the story, though, it’s told very nicely, and many of the passages are more or less identical to sections from Hard-boiled Wonderland. The narrator does end up sleeping with the librarian in the novella, which he holds off from doing in the novel.

The other critical difference between the novella and Hard-boiled Wonderland is that in the novella, the narrator escapes with his shadow by jumping into the whirlpool. He realizes what he loved was the librarian’s shadow and that time is still passing in the outside world, so he goes back. In the novel, on the other hand, the narrator realizes that the Town is all part of himself and he owes a commitment to everything there, so the shadow goes and he stays.

We know from the supplementary text in the Complete Works that Murakami rewrote the ending to Hard-boiled Wonderland after showing it to his wife, so I’ve always wondered if he had the narrator escape in that first draft.

Can I read your translation of the novella?

Absolutely not. I did it in my late 20s when I wasn’t a good writer or translator, and while it’s interesting (and helpful for me right now as I try to remember what happened in the novella), it’s not very good and I won’t be sharing it with anyone.

Do you have any theories about why Murakami named his new novel after a “failed” novella from 1980 or why he’d go back to Hard-boiled Wonderland?

I’m glad you asked! The fact that there’s an English subtitle on the Japanese cover combined with the fact that Killing Commendatore also came with a preprepared English title makes me wonder whether Murakami is already working with an English translator. We know from David Karashima’s book “Who We’re Reading When We’re Reading Murakami” that Jay Rubin is working on a new translation of Hard-boiled Wonderland. We also know from my six-year close comparison of the Japanese and English versions that there are multiple versions of that novel with small changes, not to mention the changes made by Birnbaum and Luke to their translation. My best guess would be that during the translation process Rubin asked questions about the choices Murakami made, perhaps even questions about the novella. Maybe those questions prompted Murakami to take another look at the novella, or at the very least to want to venture back to the End of the World.

Or it could be something totally different, who knows. Murakami has a long history of reworking his old stories. Hard-boiled Wonderland is a perfect example. He also used “Firefly” as the basis for Norwegian Wood, “The Wind-up Bird and Tuesday’s Women” for The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, and “Man Eating Cats” for Sputnik Sweetheart. More recently, in the 2020 story collection First Person Singular, Murakami wrote “Confessions of a Shinagawa Monkey,” which is a follow up to the 2005 story “Shinagawa Monkey.” It could be that’s just what he wanted to write about.

What do you think the novel will be about?

Hard-boiled Wonderland leaves a lot of room to expand and explore the End of the World. For example, we know that the librarian’s mother escaped the Town to live in the Woods with others who still have fragments of their mind. This is hinted at as a potential haven for the Dreamreader and the librarian. The closest they get to the Woods is the power plant, where they go to find a musical instrument from the proprietor there. He also lives an existence separate from the Town but also from the Woods. As a first-time reader, I was surprised we never saw the Woods more closely.

We also don’t know how the Gatekeeper would respond to the Dreamreader letting the shadow escape. That confrontation feels like an inevitable beginning for this new work.

The end of Hard-boiled Wonderland suggests that the data shuffling agent dies in his car listening to “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” as his inner self falls into an infinite tautology of life in the Town. I’d be surprised (and a good bit disappointed) if Murakami brings the data agent back to life. So I don’t think we’ll see him, the scientist, or his flirtatious granddaughter.

Those are my best guesses. Knowing Murakami, it will be something else entirely different. What I do think is certain, though, is Murakami will write about 街. This is an important place, one that influences the core of its residents and whose effects change as the machi itself changes.

When I was on Jenn O’Donnell’s podcast Translation Chat to discuss the translation of Hard-boiled Wonderland, she asked me whether I preferred the Japanese original or the English translation. That question didn’t make it into the final cut, and it stumped me, but I’ve mulled it over ever since, and I think I finally have an answer: I prefer Birnbaum’s “Hard-boiled Wonderland” and Murakami’s “End of the World.” Murakami achieves this incredibly subtle tone that I think can be argued is an Impressionistic, super-concentrated version of the Boku narrators in his first three novels. And if this title means that we get to spend more time in that world, sign me up.

I’ve been planning a Murakami podcast for the past month and the title announcement threw me for a loop, so I put out an emergency first episode yesterday. I have about 6-7 or so episodes planned, and they’ll be coming out at irregular intervals leading up to the release of the book. I hope you give it a listen!

いろいろ

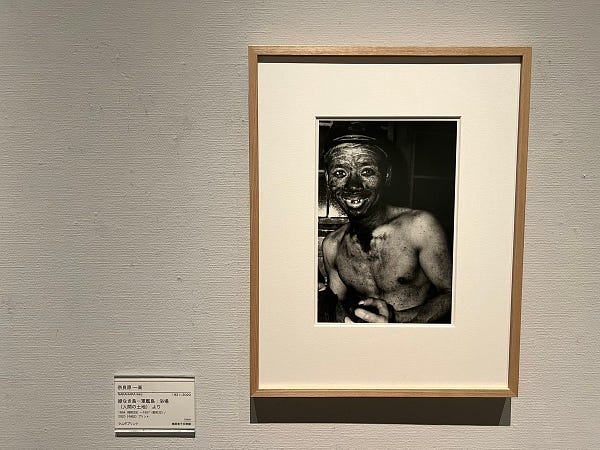

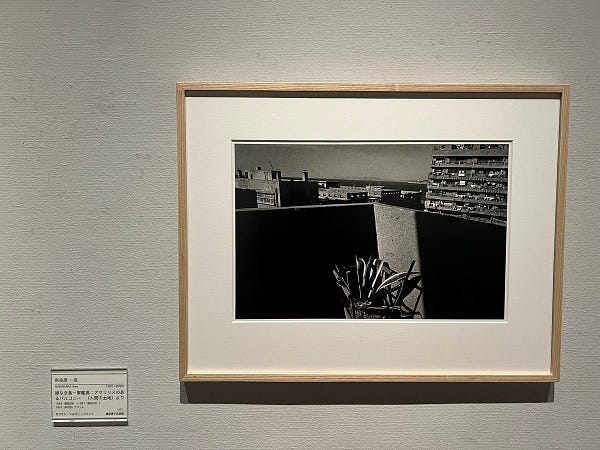

I went back to the museum in Wakayama. It’s a hidden gem, absolutely worth the trip.

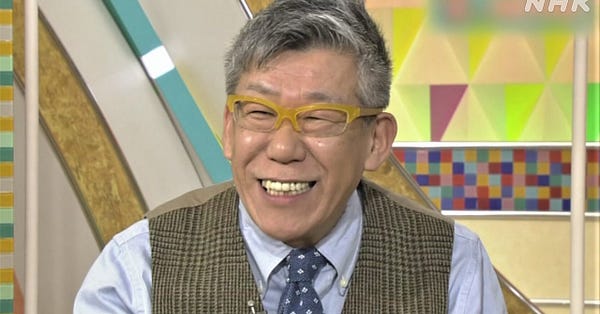

This one hit hard. Shofukutei Shohei passed away after suffering another aortic dissection. This was a nice Yahoo News story about how he suffered one in 2015 while golfing and was able to thank the woman who helped save him after he recovered.

梅 > 桜

Great read! I had no idea this novella existed. As for the English title, I've attended a Jay Rubin talk and (if I remember correctly) he talked about how Murakami wouldn't take any advice for the title Killing Commendatore, which should have been "Killing the Commendatore" as Commendatore is a title, not a name. So I can see Murakami going against the better judgment of his translators again.