コロケーション (連語)

Collocation - How to Japanese - November 2023

This is How to Japanese, a monthly newsletter with something about Japan/Japanese and a dash of いろいろ.

日本・日本語: Here

The newsletter this month will feature (quite centrally) one major spoiler for the latest John Wick movie. If you haven’t seen it and want to watch it un-spoiled, save this month’s post to read later.

Late last month I went to see John Wick: Chapter 4, which finally released in Japan in September. My month-long delay meant it was only showing on one of the smaller screens at the Toho Cinema in Umeda, which was actually perfect. Only a handful of people were there, so it felt like watching on a very large, very wide television from the comfort of my own home.

The movie itself was only OK. The first was truly spectacular, and I regret somehow missing out on the hype and waiting to stream it on my 21-inch TV in Chicago. I don’t think the subsequent sequels have captured the same magic, even if they were fun to watch and provided beautiful glimpses of places I’d like to travel someday, alongside thrilling and ridiculous gun fu.

I don’t remember much about the Japanese subtitles in the latest installment…except for one of the very last scenes, which hit me like the proverbial ton of bricks. In this final (?) mainline movie, Wick finally takes one bullet too many. The story ends at Wick’s grave with a shot of his gravestone next to his wife’s; they read “Loving Husband” and “Loving Wife.”

This is a nod to earlier in the movie when Wick parts with Winston Scott, manager of the New York Continental Hotel, and says, “‘Loving Husband,’ that’s what I want on mine.”

In Japanese, as the camera shows the grave, the subtitles read:

妻を愛する夫 (tsuma o ai suru otto, husband who loves his wife)

夫を愛する妻 (otto o ai suru tsuma, wife who loves her husband)

I wasn’t paying attention, but I assume the translator did a decent job of tying this string together and used a similar translation for the earlier conversation. No matter how you spin it, though, this translation doesn’t do the same thing as the English. The Japanese is far too narrow. “Loving Husband” in English does indeed mean “a husband who loves his wife,” but that love doesn’t feel as unilateral as it does in Japanese. It’s more expansive. It encompasses a greater range of possibilities. Perhaps unexpectedly, English is more concise here than Japanese, a language known for its concision.

But I’m not sure I can fault the translator. I understand what they did and why. I’m not sure if Japanese has an equivalent collocation. That’s what “loving husband” is in English, and why it has such a broad embedded meaning.

Collocation is a tricky word to define, both in English and Japanese. Merriam-Webster has:

a noticeable arrangement or conjoining of linguistic elements (such as words)

Cambridge gets specific to nail things down more precisely:

a word or phrase that is often used with another word or phrase, in a way that sounds correct to people who have spoken the language all their lives, but might not be expected from the meaning

The example Cambridge provides is “a hard frost.”

Japanese uses the loan word コロケーション (korokēshon), and the Nihon Kokugo Daijisen has:

(collocation) 文や句において、文法的、意味的に関連する二つ以上の単語の結合がある程度固定化している関係。また、その結合のしかたをいう。

When the combination of two or more words that are linked grammatically and in terms of meaning in a phrase or sentence become a relatively fixed relationship. Or the formation of that combination.

The Digital Daijisen is simpler:

二つ以上の単語の慣用的なつながり。連語関係。

The idiomatic connection of two or more words. A 連語 (rengo).

Collocation is, essentially, the formation of natural phrases in language, and there aren’t always perfect collocation equivalents between different languages.

However, there should be some alignment in translation. If we look at the Google search results for the following phrases, it instantly becomes apparent that the frequency is out of sync with this specific example:

“loving husband” - 9,510,000

“妻を愛する夫” - 17,900

“愛おしい夫” (ito’oshii otto, dear husband) - 5,550

The third option here is one that came to mind when I was thinking of alternate candidates, and it was confirmed as an awkward potential translation on Weblio, but it gets even fewer hits than the subtitle translation.

So what would be a good option? I’m not sure there is one. Japan has very different traditions when it comes to gravestones. Not many opt for creative engravings. Even when Japanese opt for an engraved phrase, they seem to keep things simple like ありがとう (Arigatō, Thank you), やすらかに (Yasuraka ni, [Rest] in peace), or single kanji like 愛 (ai, love) and 絆 (kizuna, bonds).

As an example, even the hyper-creative artist Okamoto Tarō went with just he and his wife’s names, although the headstone is adorned with one of his sculptures, so maybe this doesn’t count. (His mother and father’s graves face his and there’s a passage from a Kawabata Yasunari letter dedicated to the family, so this is truly exceptional.)

So perhaps there’s no way to translate “Loving Husband” into some sort of frequently used Japanese headstone engraving that would loosely equate to the same meaning.

Another reason there’s no alternative to 妻を愛する夫 is that there just don’t seem to be any equivalent collocations. There are Japanese collocation dictionaries, but unfortunately the one I have doesn’t include any phrases with 夫. And the only free, online collocation dictionary is closer to a random collection of phrases rather than a curated set of examples from the language.

Which I think leaves the translator with two options. A slightly forced direct translation, which is what we got, or leaving the English as is (rendering it into katakana?). I found this YouTube video with a dubbed version of the movie, which leaves it as “Loving Husband” in English, which is actually a pretty decent solution.

(I’m embarrassed to say I don’t know what language the dub is. If you recognize the language, please leave a comment and I’ll update this section.) This makes me wonder how the Japanese dub handled the translation.

And of course 妻を愛する夫 is probably a perfectly good translation, especially in the context of the John Wick movies. Wick doesn’t have any kids, just a dog, so “Loving Husband” here pretty much means what the Japanese translation suggests, although it still misses out on a sense of caring and warmth that I think the English expresses.

When you’re using Japanese for your own communication, however, it’s almost always best to avoid a direct translation and look instead for a natural Japanese collocation. Dictionaries like Kenkyusha’s and Gakken’s can be useful.

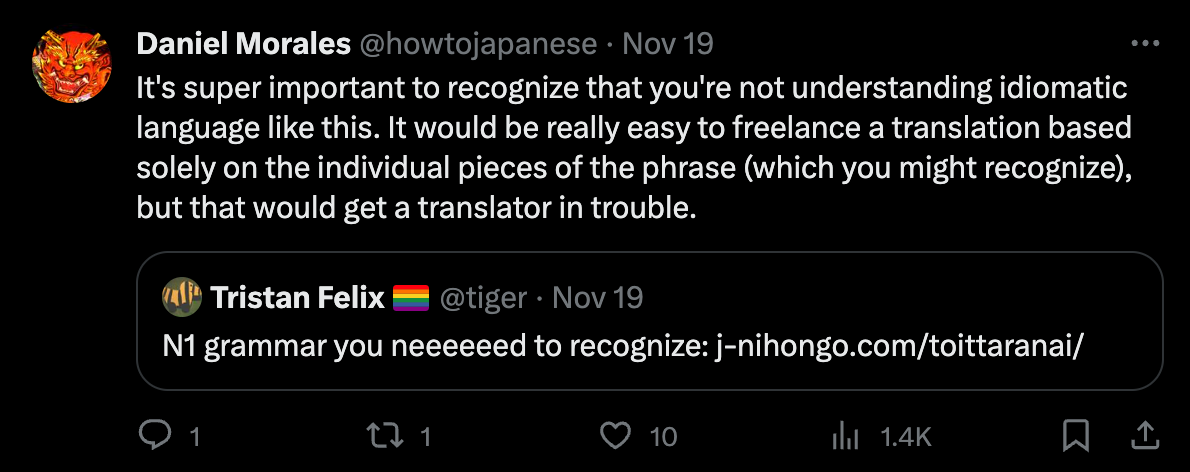

Often the most difficult part is realizing that you’re running into a collocation. If you recognize the pieces of a phrase but don’t recognize the overall meaning/structure, the odds are good that you’re seeing a collocation or idiom of some sort and should not freelance an answer.

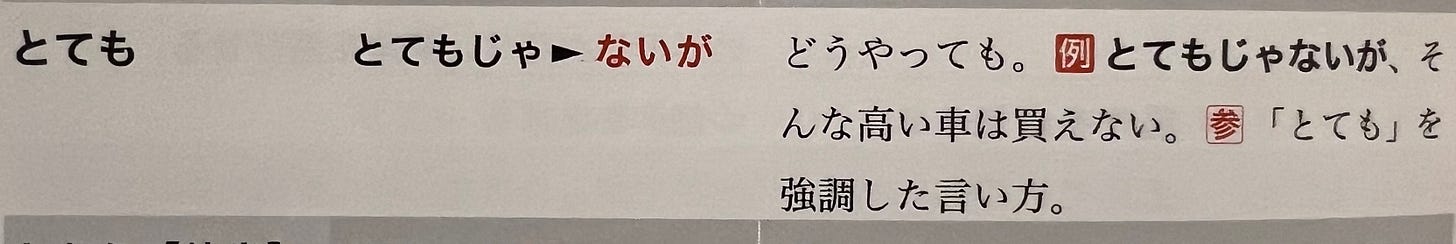

A good example from Gakken is とてもじゃないが (totemo ja nai ga). At some point in my Japanese study career, I know I would have translated this as “not very,” but as we can see here, the real meaning is actually どうやっても (dō yatte mo, no matter how/what I/he/she/they try):

What do you think of this subtitle translation? Have you used a collocation dictionary before? What strategies do you have for tracking down natural Japanese phrases and incorporating them into your own language?

I’m always on the hunt for collocations. I find them reassuring. We don’t need to (and shouldn’t!) reinvent language every time we go to have a conversation or write a letter. That’s absolutely the case with English. Check out the Google hits for the collocations I used in the newsletter this month:

“from the comfort of my own home” - 2,720,000

“in the comfort of my own home” - 1,460,000

“was only OK” - 967,000

“miss out on the hype” - 1,940,000

“captured the magic” - 5,360,000

“captured the same magic” - 31,900

“like a ton of bricks” - 1,310,000

“hit me like a ton of bricks” - 320,000

“like the proverbial ton of bricks” - 2,030

“pay attention” - 360,000,000

“a decent job of” - 2,420,000

“a perfectly good” - 5,380,000

“the odds are good that” - 200,000

This is not an exhaustive list, and I’ll admit that I’m not perfectly clear about the line between idiom and collocation, but suffice it to say that set phrases and language like this exists for Japanese as well. The goal is to acclimate yourself however you can, mostly through exposure, but also by painstakingly hunting down correct usage. Collocation dictionaries are a great resource for this, and I recommend picking one up.

Check out the podcast this month for more collocation examples from the Gakken dictionary I mention above!

いろいろ

Here’s more idiomatic language that is helpful to recognize. Link to Tiger’s original tweet.

A reminder that if you haven’t read W. David Marx’s Ametora, it just got an updated edition. We got this sad news this month. Link to David’s original tweet.

I was back in the U.S. for a week at the beginning of this month. I used an Airalo e-sim to get cell data. It was seamless and super fast. A really easy process all around. They offer it all over the world, so I’d definitely look into it if you’re coming to Japan. I plan to use it whenever I travel abroad. You can use my referral code to save $3 and chuck $3 over to me as well: DANIEL94439. As reference, I used 5GB of data over 10 days, and I’m a pretty heavy data user.