なんです

Little bits of language - How to Japanese - June 2025

This is How to Japanese, a monthly newsletter with something about Japan/Japanese and a dash of いろいろ.

日本・日本語: なんです

My wife loves Hoshino Gen. I myself am not really a fan, but I’ve been trying to not not develop an ear for his music…if that makes any sense at all. A lot of his songs sound very similar to me at this point, but as we were watching one of his concerts on Blu-ray recently, there were one or two that stood out to me. I’ll have to track down which ones they were…

However, there is one thing that I will never forget about that concert. During one of the interludes, Hoshino took a moment to talk with the audience. I don’t remember what the setup was, or maybe this was the setup, but at one point, he looks out at the audience and says simply: 誕生日なんです (Tanjōbi nan desu, It’s my birthday).

That’s it. Just that short little phrase. He then continues on with the banter, but this was a statement phrase, the start of something. And it felt like the perfect example of how to use this なんです there at the end of the sentence, which is notably different from just です, so I wanted to write about it this month.

What’s going on here? Why doesn’t he just say 誕生日です (Tanjōbi desu, It’s my birthday)? As you can see, I’ve used the same basic English translation for both of these expressions. Are they not more or less equivalent?

They are not.

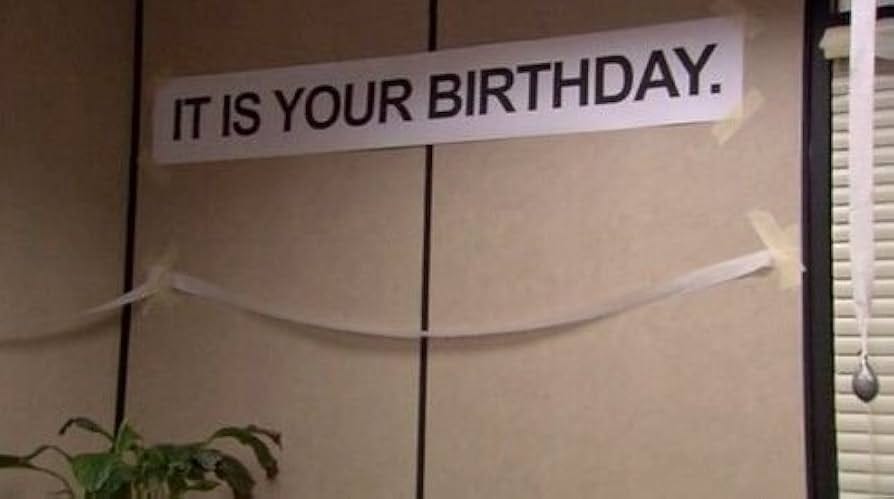

There is a perfect was to capture the regular, vanilla 誕生日です, and that is with this image from one of my favorite episodes of The Office:

In this case, however, instead of “your birthday” it would be “my birthday.”

It is my birthday.

It. Is. My. Birthday.

No contractions allowed. No facial expressions either. A perfectly Dwight-Schrute delivery is all that’s allowed.

What does なんです add? Let’s take at a look at a definition, and in this case the Kotobank definition just calls it a polite, spoken version of なのだ, so we’ll check out the definition of なのだ:

説明、または強い断定の意を表す。

Expresses explanation or strong declaration.

なんです adds in everything else. The contraction. The facial expressions. And a lot more conveyed a-lingually.

In English, the only way to capture this would be to add some additional, similarly subtle verbiage: “So today’s my birthday.” Adding a “So” here at the beginning of the sentence actually mimics what’s going on here pretty well.

This pattern attaches directly to nouns and な-adjectives:

N + な + の/ん + です

In the spoken form, の becomes ん. The です can be in any form: だった (datta) or でした (deshita) to talk about something in the past, である (de aru) if you are using it in written form, だろう (darō) if you are conjecturing or talking about something in the future, and many others.

So how might we use this? Can we just attach it to any noun (Yes) or do we need to use it in specific circumstances (also Yes)?

Combining なんです with 実は (jitsu wa, actually) creates an easy-to-use structure that I think will help solidify the role of this little nugget:

実はXなんです (Jitsu wa X nan desu)

Actually it’s X.

Here are a couple of nice examples I found on the website formerly known as Twitter, still one of the better corpuses of Japanese out there:

Here the author sets up expectations with the photo of a (somewhat) green cityscape and funicular (?) tracks and the text 自然が多い所にいます (Shizen ga ōi tokoro ni imasu, I’m in a place with lots of nature) and then subverts them by saying 実は東京なんです (Jitsu wa Tokyo nandesu, Actually this is Tokyo). Here the なんです helps apply some of that subversion pressure along with the 実は.

So if you’re a Canadian living in Japan and constantly being confused for an American, when someone asks about your hometown and implies that it’s the U.S., you could say 実はカナダなんです (Jitsu wa Kanada nandesu, Actually it’s Canada).

Here’s another example, this time without 実は but another expectations subversion that takes advantage of にとって (ni totte) and は (wa) to draw a distinction:

猫たちにとって玄関は楽しい遊び場なんです! (Neko-tachi ni totte genkan wa tanoshii asobiba nandesu, For cats, the entranceway is actually a fun place to play!)

So my official recommendation is to add 実はXなんです to your list of memorized phrases and then start to work it into your speech patterns when possible. Soon enough, you’ll have a natural feel for when you can jettison the 実は and use なんです all on its own.

And by that point I think you’ll start to see the same thing works for adjectives and verbs as well, except you don’t need the な:

ADJ/V + の/ん + です

So if someone asks you why you haven’t splurged on a new Nintendo Switch 2, you can respond with a simple 高いんですよ (Takai ndesu yo, Because it’s pricey).

Or if someone asks whether you ended up following through on your plans to go to the Osaka Expo, you could say 行ったんですが、ずっと雨だったんです (Itta ndesu ga, zutto ame datta ndesu, I did go, but it rained the whole time). Here you have the double usage after the initial verb and then after 雨.

We had the NBA Finals at the beginning of the month, so allow me to use a basketball analogy. Most sports fans follow the ball when they’re watching a game, but so much is going on away from the ball. This is obviously true with a sport like American football where the are 20+ players on the field at any given time, but it’s also true for basketball, which takes advantage of slight movements to create openings for easier baskets. One thing you can do as a spectator is pick a player (maybe one of the role players) and focus on that player rather than the ball. What are they doing when they don’t have the ball? How do their movements affect the rest of the game.

The same is true with なんです, and I’d argue for のだ as well, which I wrote about previously. These are not always the bits of the language that we focus on when consuming Japanese media. I’d challenge you to spend the next couple weeks or months keeping a lookout for these little phrases and how they get used. See if you can follow them around instead of “the ball.” These little interstitial explanatory bits of language will get you closer to sounding more natural in Japanese and to understanding what’s going on with the language when you’re watching a show or reading a book.

いろいろ

Over on the blog I have managed yet again to blog about Murakami. Just a quick interstitial chapter as I get caught up on my reading of Distant Drums, still one of Murakami’s most interesting untranslated works. Someone please pay me to translate it!

The podcast is online as well.

I started playing Metaphor: ReFantazio. I’m only three hours in and am enjoying it, but the translators do seem to be replicating almost every instance of ellipses at the start of a sentence in the Japanese, which is one of my irrational pet peeves. I don’t think English should be locked into the same structure as the Japanese, and anchoring to an ellipsis does exactly that.

I mentioned basketball as a metaphor this month, which reminds me that I have not yet recommended Rakuten’s mobile phone service. It’s cheap, the connection is decent (although I hear the connection is poor in Tokyo subways), and you get free NBA League Pass. It’s kind of incredible. There’s a dedicated League Pass smartphone app and an app that works on my smart TV. You get access to every game. I managed to catch some of the NBA Finals on my lunch break and many of the weekend playoff games.

This was a good post, and it didn’t get enough attention lol

Happy Pride.

In other Japan recommendations, I can recommend the Adidas online shop for buying large shoes. I am cursed with narrow, flat, size-13 feet, which is 31cm in most Japanese sizes. I ordered a new pair of gym shoes, and Adidas delivered them almost next day. You can search their website by size, which makes it easy to determine what’s actually available.

Mulboyne did the hard work with this.

What made you choose to play Metaphor in English instead of Japanese?

This is great, Daniel. Because I study myself and don't have any humans to ask questions of (one of those "downsides to social isolation in a post-COVID world"), I don't know why I haven't been subscribed to your Substack before; but this is precisely the kind of thing that helps with reading no end! Thank you.