This is How to Japanese, a monthly newsletter with something about Japan/Japanese and a dash of いろいろ.

日本・日本語: Here

まとめる (matomeru) is another word that solidified for me only recently. I’m sure I’d heard it and even used it in the past, but I could viscerally feel my understanding of it click into place, so to speak, when I saw it as the “conclusion” to academic papers during my time at IUC.

The デジタル大辞泉 (Dejitaru daijisen) gives three definitions for the word, and the first is the most concrete and likely the one that students will encounter first:

ばらばらのものを集めてひとかたまりのものにする。

Collecting separate things and making them into one (mass/lump).

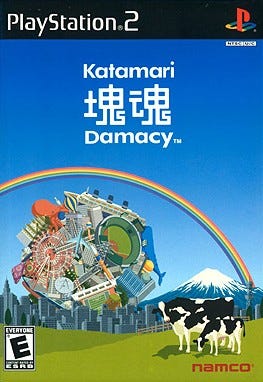

You may recognize part of that word ひとかたまり (hitokatamari, one lump/mass) from the Namco game Katamari Damacy. This association might even serve as an expedient for understanding what まとめる means: Bringing objects together into close physical proximity, sometimes even combining them into the same thing.

(On a total sidenote, has anyone written about how Katamari Damacy is one of the all-time great titles for any piece of media in any language ever? I have quibbles with the English romanization, but the Japanese title? I mean, just look at it!

塊魂

The genius becomes truly apparent when you see how it’s displayed on the box art.

)

I think まとめる has been on my mind because of my recent move, during which I was literally まとめるing my 1LDK life into boxes and bags and moving it to a different part of Osaka.

But definition number two is the real reason I’ve had the word sitting with me the past couple years:

物事の筋道を立てて整える。

Establishing and putting into order the reasoning of things.

This is a more figurative meaning of the word, but it follows pretty naturally using the physical definition as a metaphor: All these ideas are all over the place; here, let me show you how they all relate. Ideally, this is what a writer does at the end of a piece of writing, thus the noun form of まとめ is used as conclusion.

The final definition is another more conceptual, less physical usage:

決まりをつける。互いの意志を一致させる。

Coming to a settlement. Putting everyone on the same page.

So rather than physical objects or reasoning, you can also use まとめる to “align” people’s thinking, which also makes sense given that first definition.

The more you look around, the more likely you are to encounter this phrase in your daily life in Japan/Japanese. I saw it the other day on メルカリ, which I mentioned last month: まとめ買い (matomegai, bulk purchase) is an option that sellers can used to give buyers the option of buying multiple items from them at the same time.

Once you’ve mastered the 他動詞 (tadōshi, transitive) version, you should also try to wrap your brain around the 自動詞 (jidōshi, intransitive) version: まとまる (matomaru, to be brought together/collected, to be arranged/in order, to be settled/resolved).

自動詞 are, on the whole, more difficult to come to terms with, so I wanted to give you three phrases with examples from social media that will hopefully prime your brain to take in other usages.

きれいにまとまった (kirei ni matomatta)

Came together nicely

This first one is, I think, relatively easy to understand and follows naturally from the 他動詞 definition. In this tweet, the author writes about how nicely his Strike Freedom (ストフリ) Gundam has come together. There’s the physical sense of pieces coming together into a single object with this phrase that makes it more tangible. Note that the 自動詞 is used despite the fact that the writer is likely the person who did the まとめるing.

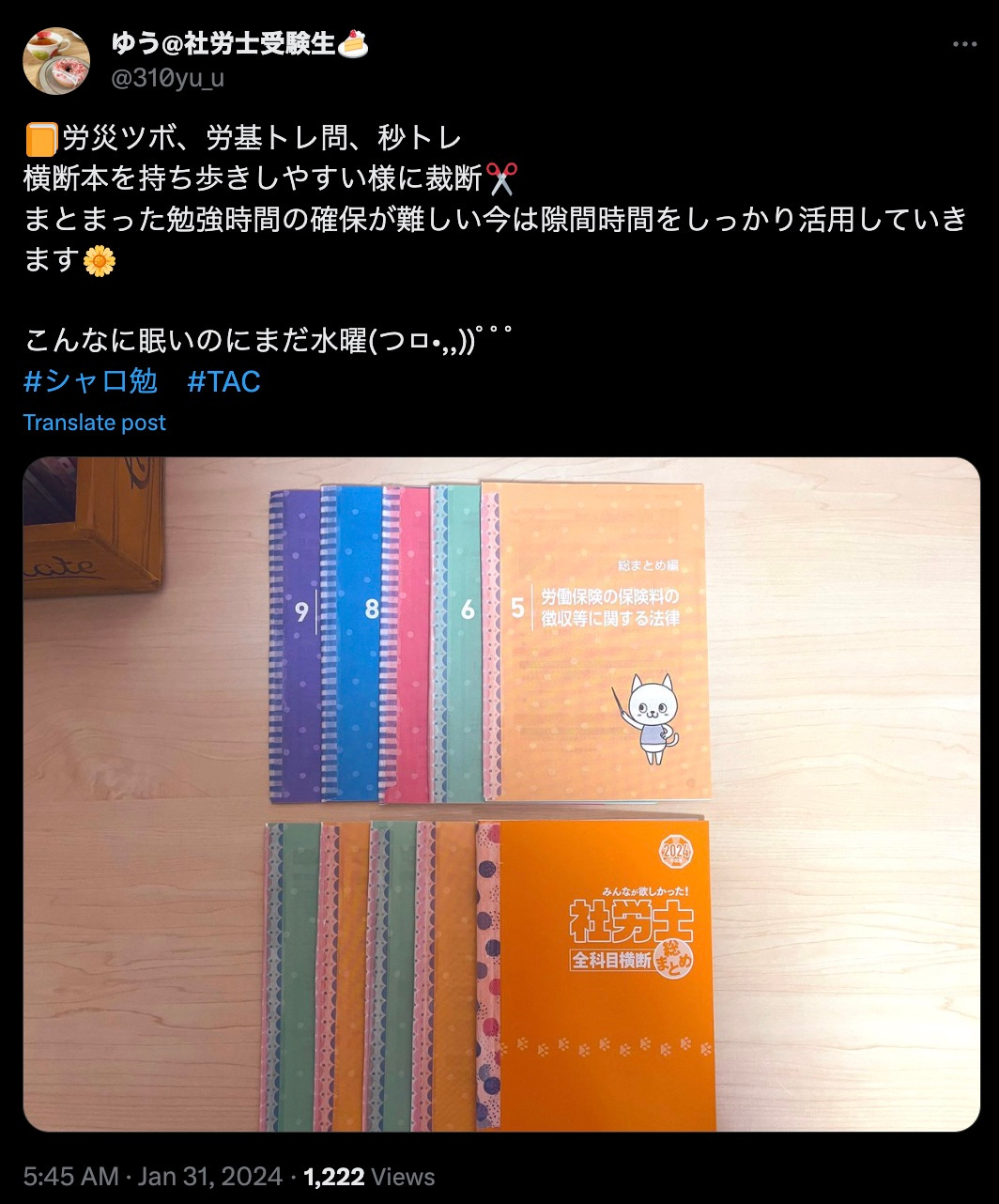

まとまった時間 (matomatta jikan)

An undivided period of time

Here’s someone studying to become a 社労士 (sharōshi, labor and social security attorney). They note that まとまった勉強時間の確保が難しい (matomatta benkyō jikan no kakuho ga muzukashii, it’s difficult to secure an undivided period of time to study), so by setting out all the textbooks as in the photo, they can use 隙間時間 (sukima jikan, spare moments) to fit in study. The contrast here between まとまった時間 and 隙間時間 makes it easy to understand, and “undivided” is a nice way to render this naturally in English, although you could also go with “a big chunk of time,” depending on the context.

なかなかまとまらない (naka naka matomaranai)

(Something) doesn’t come together

In this tweet, the writer has just seen the movie Silent Love, but they aren’t quite sure what to make of it yet: 感想がなかなかまとまらない (kansō ga nakanaka matomaranai, my thoughts aren’t coming together). So rather than a physical Gundam or the less tangible time, here it’s the invisible thoughts themselves (ideas!) that won’t form into some comprehensible state. I like the efficiency of the phrases in this tweet: 頭整理中 (atama seiri-chū, literally: “I’m currently organizing my head,” i.e. I’m getting my thoughts together).

Equipped with these three phrases, hopefully you’re ready to express your thoughts, whether or not you’ve had a minute of undivided time to get your thoughts together so early in the New Year.

いろいろ

Dr. Wes Robertson is on TikTok (@scriptingjapan) and predictably it’s great content. If you don’t follow him on social media, he researches and teaches Japanese language and is working on a free Japanese textbook. He mines Twitter to find usage examples and trace the developments of the Japanese language. Here he’s looking at whether or not you can verb different nouns in Japanese. Really fascinating stuff.

And in a funny coincidence, one of the words from this month’s newsletter—まとめ買い—comes up in a video here about the phrase 大人買い (otona-gai, lit. “adult buying” i.e. buying everything in a category/buying lots of one thing). Check out his TikToks!

Moving into a larger apartment in Osaka has been kind of eye-opening. For the longest time, I was basically locked into the least expensive option in Japan. The cheapest, smallest room, with many roommates. The cheapest bentos. But that hasn’t been the case with my most recent time in Japan. I managed a reasonably sized apartment—a 1LDK—before my current spot, and I probably should have gone even one bedroom larger. Having the extra space is so nice. If you can, try to get that extra space. It makes a major difference. Especially if you like to cook. My last place had the kitchen of a 1K in a 1LDK. Now I finally have reasonable counter space. What a difference it’s made. However, moving can quickly cause major GAS (gear acquisition syndrome). If you get a bigger place, you need to fill it with expensive stuff. Sofas, beds, fridges, microwaves, yada yada. Or you can find some sort of middle ground, which is what I did with my first Osaka apartment: Instead of buying a bed, I used a foldable mattress.

I think mine ran me about 30,000-40,000 yen, which is somewhere between the dirt cheap futon I slept on in Tokyo and the regularly priced bed I just bought for my new spot. Foldable mattresses store away cleanly in a closet, which opens up space when you’re not asleep (assuming you can commit to putting it away each morning). They also buy you some time. You can live in your new space before committing to the real estate of a bed. And once you buy a bed, you can always keep the mattress for guests to use.

When I moved apartments, I also had to find a new barber. My last place was near a couple small shopping arcades, so there were easily 4-5 different barbers to choose from. I rarely had to wait. My new spot isn’t quite as fortunately located, in terms of barbers, but I did manage to find a decent spot and got the best cut I’ve gotten in Osaka for 1,700 yen. This got me thinking about the 1,000-yen haircut vs. the 2,000-yen haircut in Japan. How do they hold up in terms of value? I talked about this on the podcast this month. Give it a listen over on the blog!