漢字

Kanji strategies for rookies and veterans - How to Japanese - July 2023

This is How to Japanese, a monthly newsletter with something about Japan/Japanese and a dash of いろいろ.

日本・日本語: 漢字

Well, I finished Tears of the Kingdom a week ago and I feel a little out of sorts, unsure of what to do with myself. It’s nice to take a breath and regroup. This is the first time since February that I haven’t been reading a Murakami book, writing something about a Murakami book, or playing Tears of the Kingdom. I still have a lot to finish up, and I plan to spend more time with the game (Bring me DLC, Nintendo!), but after 115+ hours, it will be good to get a little distance to reassess…life, the universe and everything, I guess.

Unfortunately, distance is also what I’ve had from my kanji practice as well over the past couple months. I’m stumbling across the finish line of two years of intense kanji study…and I will blame both Murakami and Zelda. “I would’ve gotten away with it if it weren’t for you rascally kids!”

Getting thrown off a course of study is something that will happen to all students at some point, so I thought I’d take this month and write out a few thoughts about kanji in general and SRS (spaced repetition software) programs, how I got onto my current course of study, and how to respond when you’re thrown off course.

If you’re just starting your Japanese study, you should absolutely be using an SRS of some kind.

When I first learned about the existence of SRS—I was living in Japan, using Japanese more or less fluently, already having finished a college Japanese program—I had this moment of intense psychic pain: I wanted something like this the whole time I was in college and just didn’t know how to make it myself! Ahhh!

I think what kind of deck(s) you’re using and whether you’re making the deck(s) yourself will vary by individual, but this is a technology that you should take advantage of at some point during your studies, even if it’s just to give yourself a leg up on the hiragana and katakana during your first month.

Because of where I am in my studies, I haven’t had much success building a deck on my own in the past. I’ve tried a handful of times, although I believe most of my attempts came before I had access to a smartphone app SRS, which is a true game changer. I can see it being very easy to create a deck:

- If you have the ability to get repetitions easily and quickly on your phone during down time.

- If you start using it early on in your studies.

- And if you add to it consistently based on a textbook, daily phrases you encounter, or even reading material like novels and short stories.

This is especially true if you’re wired like a programmer/database expert (because building a deck is basically creating a database with a set of rules) or are just super organized.

On the other hand, there are already a lot of really good decks out there, so if you’re looking to save the time or are not naturally wired like a programmer, I think you can easily go with pre-made decks.

My current approach has been relatively simple in that I only use Anki to study kanji (and vocab, in a sense). I’m not using it for grammatical patterns or longer phrases/sentences, although I briefly dabbled with a deck for classical Japanese grammar. I’m sure SRS can be extremely helpful for those situations, but I also feel like bulk exposure out in the wild (i.e. using Japanese as much as possible to read, write, listen, and speak) beats SRS almost any time of the day. As translator Matt Treyvaud has so poignantly stated, “Just lounge around Lemnos eating grapes, and before long you’ll grow a golden fleece of your own.”

It’s critical to recognize that SRS excel at building passive recognition. This is why it’s important to…

Think about ways to create active learning from your SRS practice.

Yes, early on in your studies—and by this I mean just the first couple months—you will probably need to prioritize recognition and passive reception of information (differentiating sounds and written scripts), but after that you need to be producing as much Japanese as possible. You’ll obviously be making lots of mistakes, but that’s fine.

This is true for kanji as well. Or I should say it used to be true. SRS are a simulacrum, a futile attempt to recreate a state in which you are regularly producing kanji by hand. If you lived 200 years ago, you’d be a living SRS. The act of writing itself is the act of remembering, and not the other way around, which the language industrial complex has convinced students is the case.

So how do we create opportunities for active production of kanji? I think the first and simplest is to write them out on paper. Don’t rely solely on your smartphone or tablet screen. It’s just not the same.

The other way is to…

Switch up the deck so that the prompt is in English and you have to produce the Japanese.

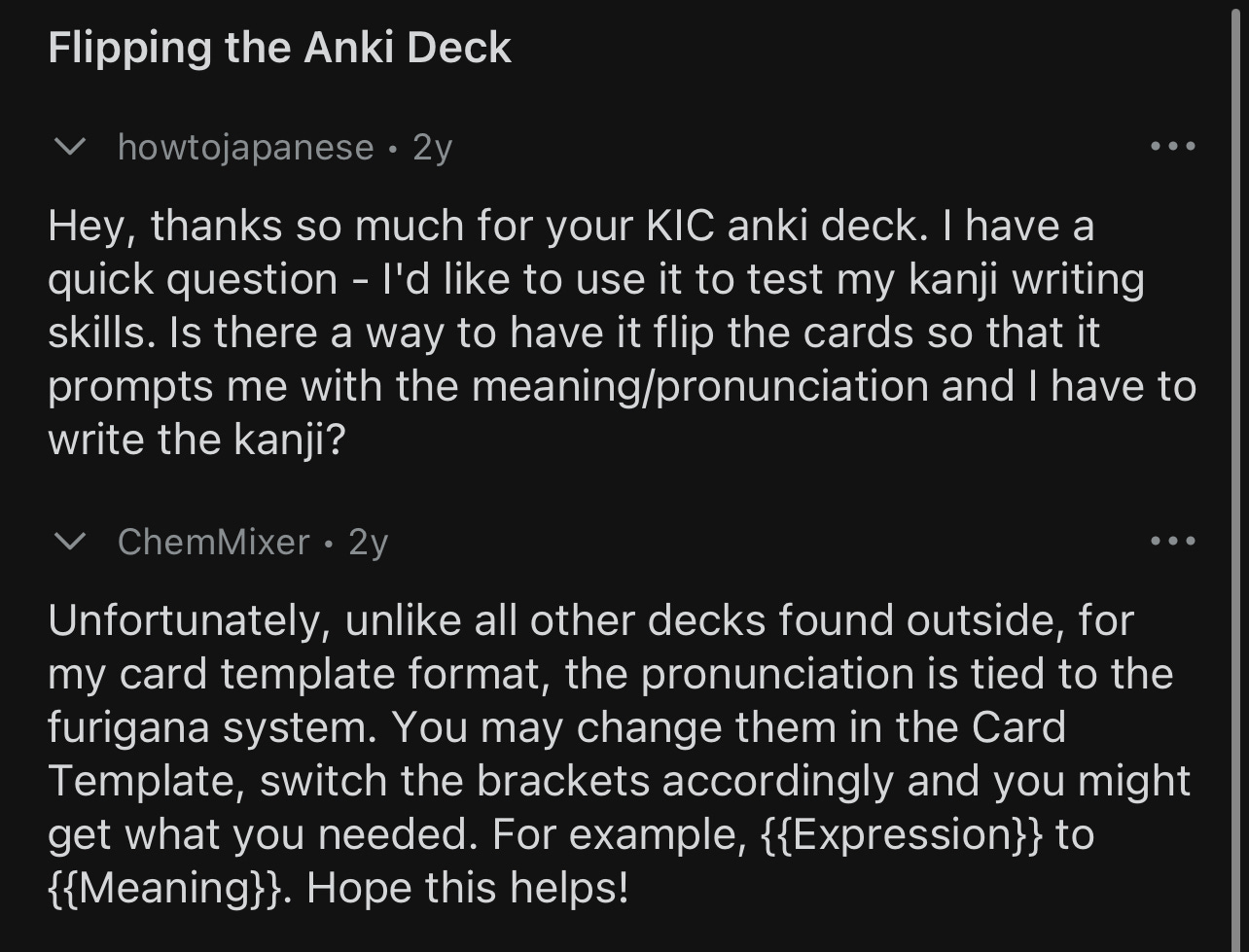

Most of the Anki decks I’ve seen give the Japanese characters as the clue/hint, and the student then has to provide the English definition, the pronunciation, or both. I knew going into my program at IUC that I wanted to strengthen my recollection and writing of kanji. Decks that showed me Japanese would not create opportunities for me to write kanji. I wasn’t sure how to adjust this, but it felt like it shouldn’t be too difficult to change, so I reached out to the creator of the deck I was using, which is based on the IUC textbook Kanji in Context. He responded really quickly and kindly over Reddit.

I’m not sure if there’s a way to do this through AnkiWeb, but in the Anki mobile app, open the deck you’re working with, click the gear icon, and then select Card Template, which will display what information from the card gets displayed.

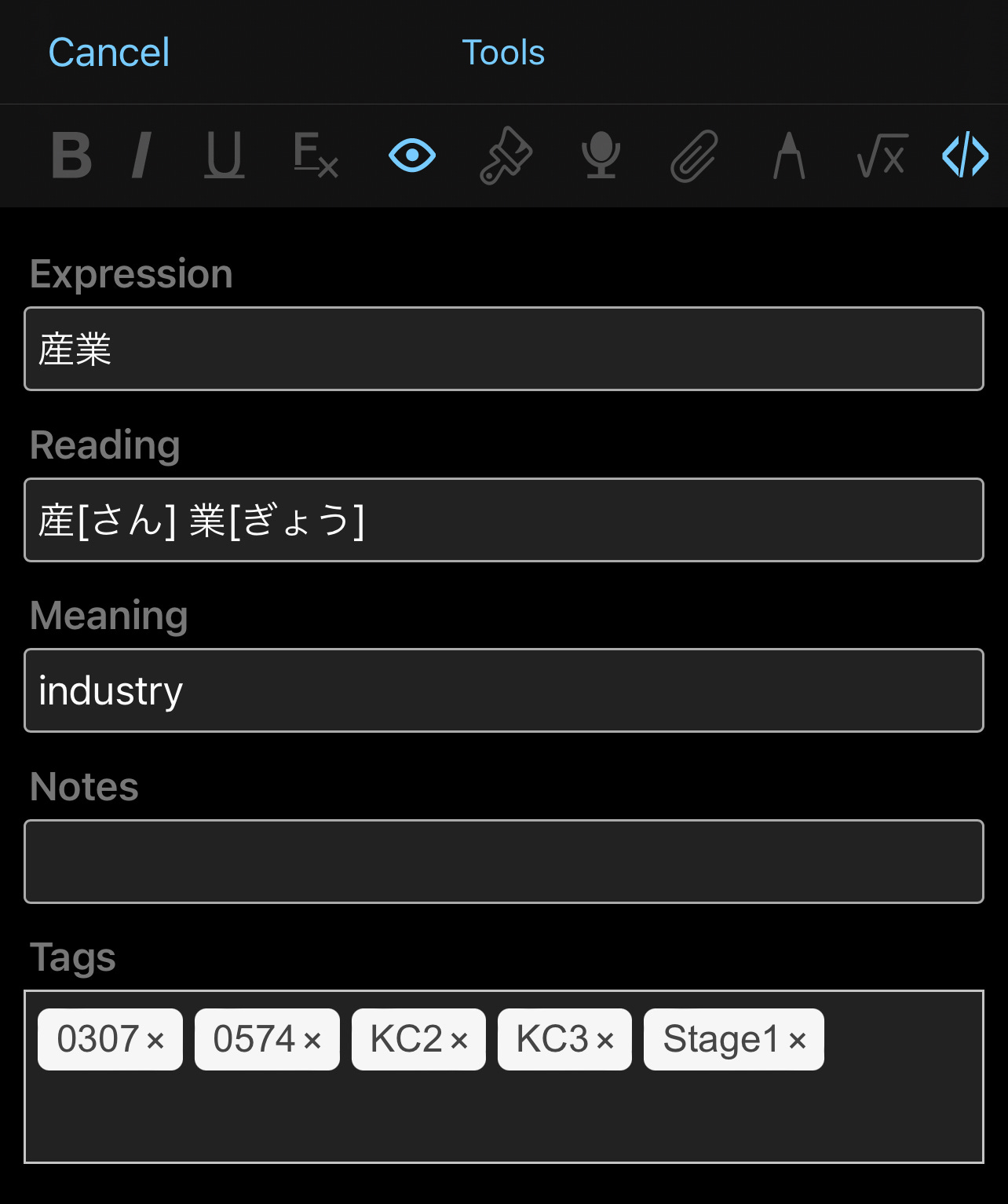

Here’s what each card looks like:

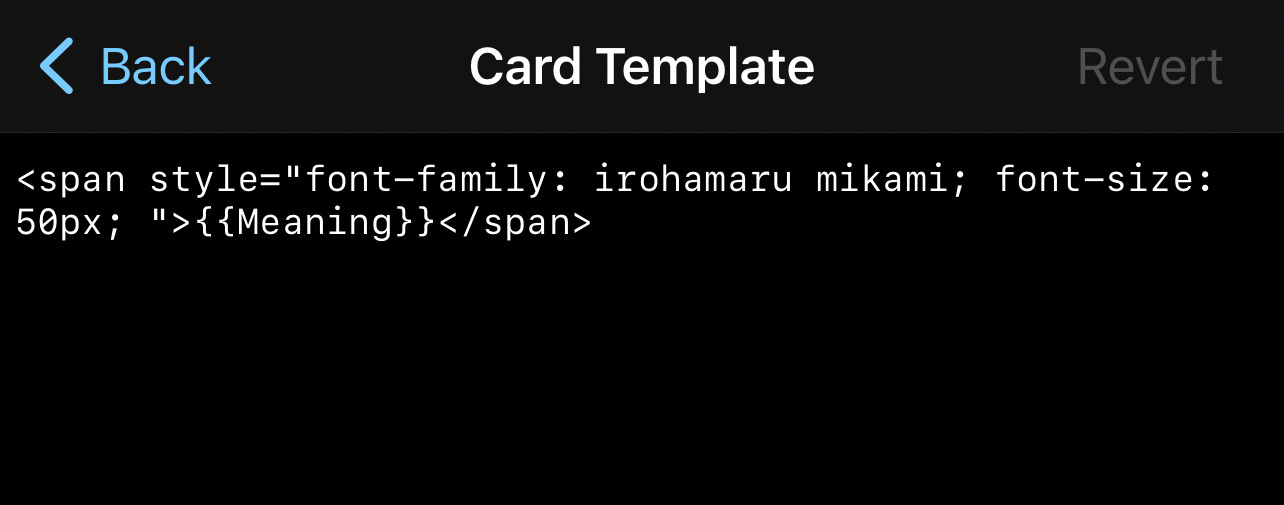

And here’s what my Card Template looks like after I exchanged {Expression} for {Meaning}:

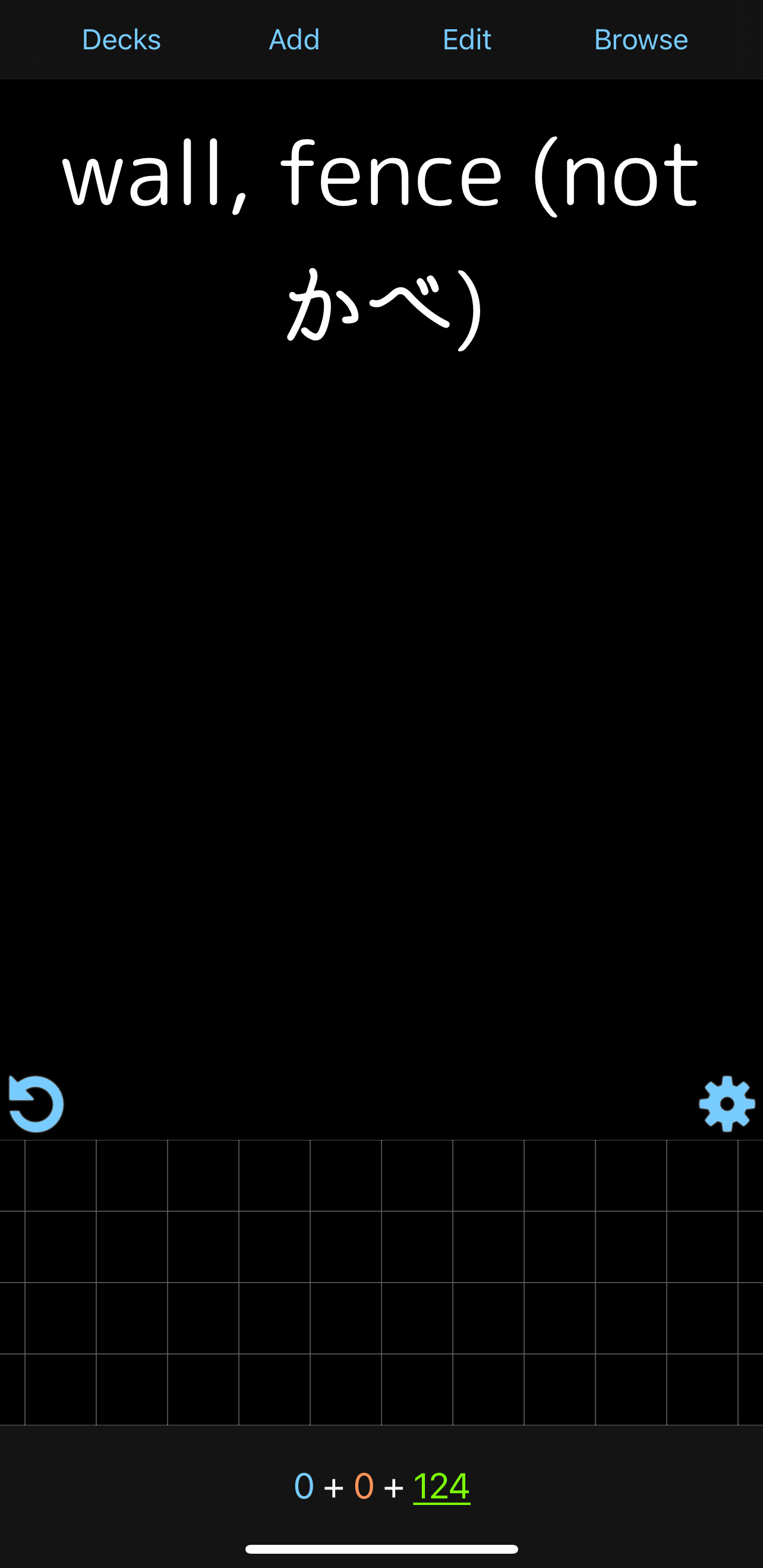

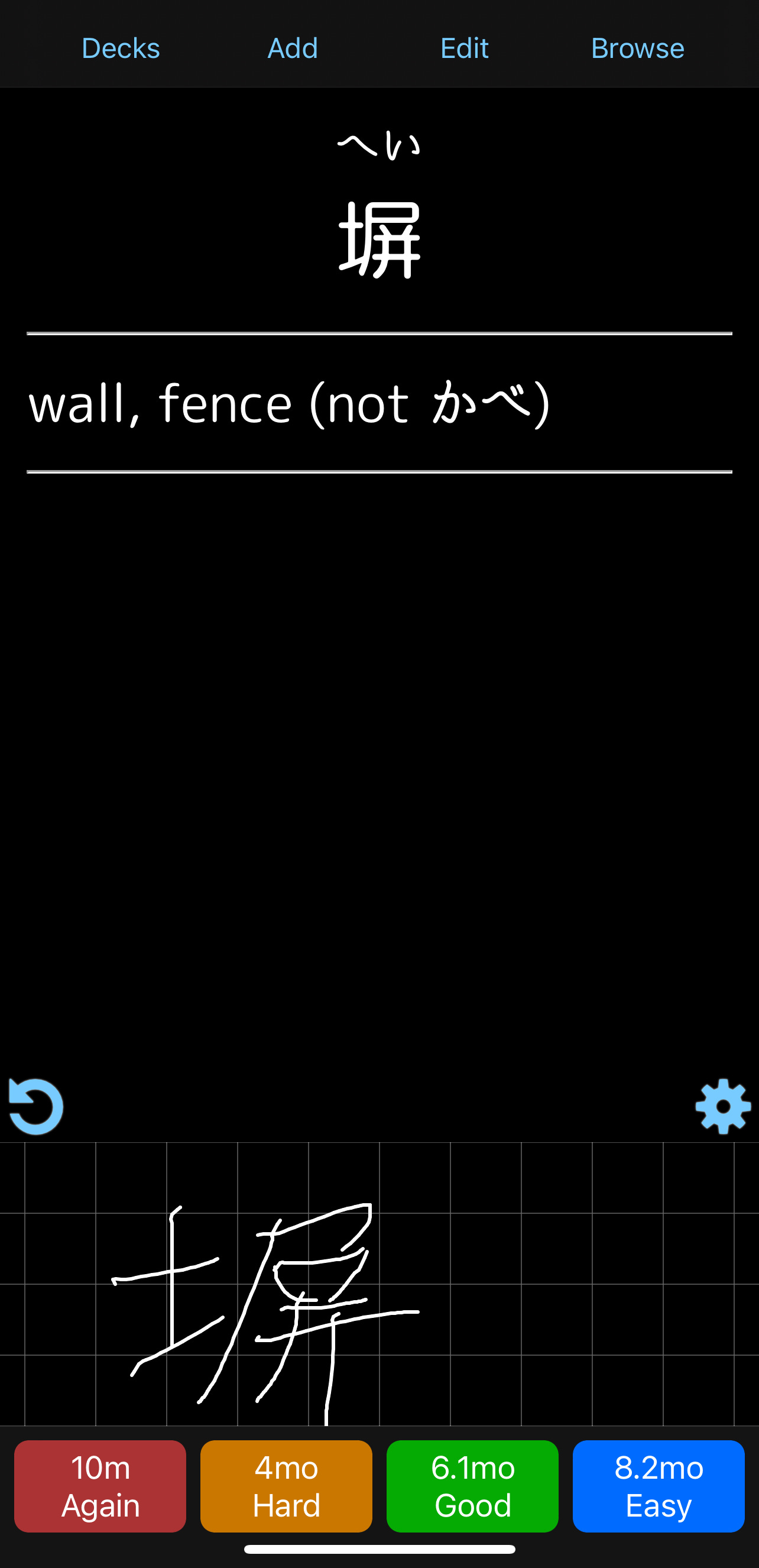

So when I load up a deck, it looks like this:

This is what it looks like after I’ve written the kanji (ignore my fat-fingered writing, pls and thnk you) and tapped to reveal the answer:

I highly recommend using this method because you’ll be getting a double dose of 勉強; not only will you be forced to write the kanji, you’ll also be forced to generate the word itself from memory. Because there are words that often overlap, such as “wall” above, as I studied the deck, I would tap the edit button and add little hints for myself using hiragana. So I knew that I shouldn’t answer 壁 (kabe, wall) in this case.

I think most SRS decks should probably be switched some way so that you’re producing actively rather than recognizing passively, unless you’re preparing for a very specific course or test (*cough* JLPT *cough*). Or maybe you need multiple decks for different situations? One for passive recognition of kanji that you can kind of zip through, and another for active production of kanji that you slow down with. If you test out this strategy, please report back!

But I can’t recommending spending too much time with SRS. They’re a bit too sterile. You need to be out there bumping elbows with real Japanese as much as possible, not just individual kanji or kanji compounds.

Doing SRS flashcards alone is not enough.

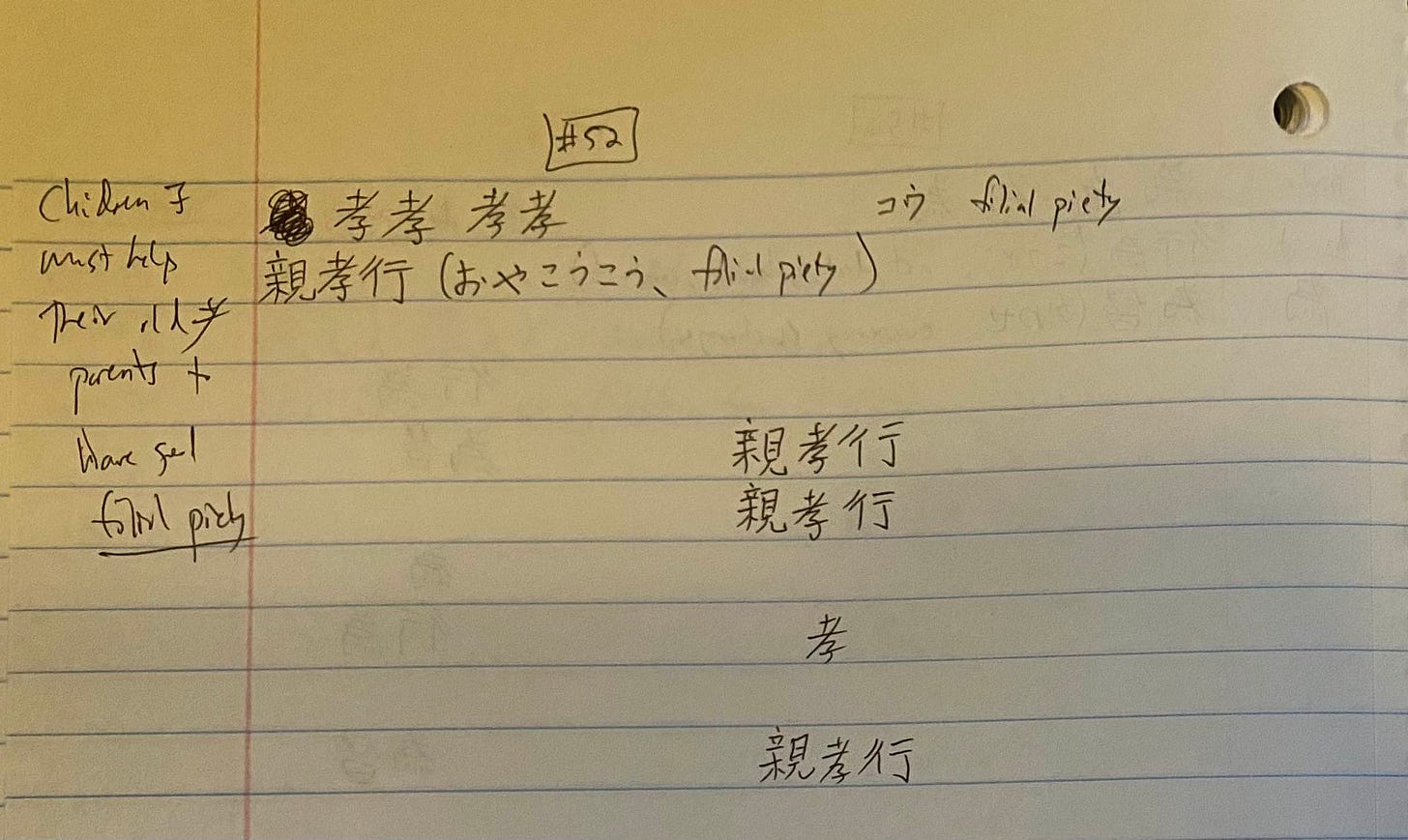

In addition to going through Anki, I also kept notebooks for the kanji and set a pace. I can’t remember exactly what it was…I think it was about 10 a day because that’s what Kanji in Context has for most of the lessons (until it brutally ramps up to 20 in each lesson at the end). I wrote out each kanji by hand, wrote out some of the example compounds and pronunciations, and practiced a few times. After a month or two, I realized I needed a little more and started generating a mnemonic for each kanji.

I can’t remember all of these, so this goal wasn’t a 100% success, but there are enough that I do remember that it was worth it. Like “Nine turkeys in a tree” for 雑. And I’ve got names for some of the radicals that I didn’t have before (like “turkey” for the right side of 雑).

I used a combination of Kanji Damage and Joy ‘o Kanji to create these mnemonics. I recommend doing the same, although this is easier if you start from the beginning of your studies.

Dabbling is not recommended.

I do think it’s worth setting a goal with kanji. Set a pace for yourself and try to keep to it. I don’t think I would’ve been able to keep up half the pace I did over double the time, but because I knew it was a short term pain, I was able to muscle through 10 months of it. This will probably contradict the advice I’ll give later, but here’s what a reasonable pace might look like: If you can do kanji at a 50/week pace, that’s 42 weeks for all 2,136 常用漢字 (jōyō kanji, common use kanji), 10 weeks short of a full year. That gives you weekends to recover and solidify what you’ve studied, and 10 weeks of room to inevitably fall off and then get back on your course. I think that would give you a good foundation for future studies, especially if you maintain your base SRS practice moving forward through subsequent years of study.

Set a limit on how many repetitions you do a day is critical.

I don’t know what the maximum repetitions would have been in my case, but I ended up setting a limit of 200 cards/day. I would add new cards equivalent to 10 kanji each day, reset the number of new cards to zero, and then practice 200 repetitions due that day. That was enough for me.

I also did SRS while watching TV shows and listening to podcasts/music, both Japanese and English. I found this to be a pretty effective way to ease the pain of powering through it. I seemed to be able to get through my kanji study in an hour or two each day.

Spelling English words is (maybe?) as difficult as writing kanji.

One of the realizations I had while going through this exercise is that English is no different than Japanese on many levels. Yes, kanji feel more difficult and take a focused training that maybe Western languages don’t in order to be able to write the language, but spelling in English is, I think, just as complicated as kanji in many ways. It requires memorization of obscure rules, for which there are countless exceptions with bizarre etymologies. It requires specific training in school. (I remember third grade vocab tests very clearly, for some reason.) Mnemonics help! (“I before E except after C” etc.) And a lot of it kids will pick it up on their own by burying themselves in books that they have fun reading.

I see a lot of similarities between spelling and stroke order, with one massive advantage for spelling: You get the spelling repetitions even while entering words digitally into a computer, whereas you cannot get stroke order repetitions this way. If only! Imagine if you had to somehow type the stroke order into the computer to generate the kanji. Imagine how many more repetitions you’d get! Every time you type out an English word, you’re remembering how to produce it. The act of typing English is the act of remembering. Every time you type a Japanese word, you only need to remember how it sounds. The act of typing Japanese is the act of remembering how it sounds.

You’re never too old to learn kanji.

I managed to refresh my kanji practice at the ripe age of 40 and kept it going for nearly two full years. I was already able to read Japanese fluently before starting this exercise, but I can honestly say that it’s been hugely beneficial for my reading ability as well. There are so many words that are more accessible, compounds I understand more quickly or more generally even if I don’t understand them completely, and because of the way Kanji in Context is organized, I also recognize the pronunciation of single-kanji verbs like 慕う (shitau, yearn for, long for) or 募る (tsunoru, grow in intensity). (Actually, I learned that last one from enka ^^;)

On the other hand, I whiffed both 偽る (itsuwaru, deceive) and 苦悩 (kunō, agony/anguish) back to back in the reading group this month.

So get started now. Pay the money for the Anki mobile app, find a deck, set a goal, and get going.

Would you recommend Kanji in Context?

Yes, I think I would, and not just because I attended IUC and was in a Stockholm syndrome situation with the book. Kanji in Context organizes the kanji in what feels like a really considered way. I’m not sure if it’s the best way, but it feels more optimized for non-native language learners than the order of the 常用漢字. Kanji with similar radicals get grouped together in bunches, and the vocab examples cover most pronunciation possibilities (although obviously not every single one): generally a compound or two and the main verb that uses the kanji as a stem.

You can find the Anki deck for the textbook here, so you can basically get started without even owning the book.

Don’t be scared to “zero out.”

I probably have a backlog of around 200 or so cards that I need to review in my Anki deck. If you’ve ever found yourself in this situation, you might be familiar with the dread of not only digging back through all those cards but knowing that you’re about to mess up a ton of them, which will send them to the top of your stack to review the next day.

Sometimes you have to go easy on yourself, and in times like this I think it’s perfectly acceptable to “zero out.” This is reviewing the card, doing the ones you can, at least writing them for practice even if you can’t remember them, and then marking them as “Hard” instead of “Again.” Marking a card as “Again” in Anki will make you repeat it again that day and the next. Giving yourself too many “Again” can snowball and defeat your will to review the deck the next day.

So just mark them all “Hard.” This will show you the card again more quickly than otherwise but not that day or the next day. It gives you a bit of a reprieve. The important thing is that you wrote the kanji that day. As long as I’ve written the kanji that day, I feel my job is done, and I can give myself a reprieve for now. Make sure to take it easy on yourself.

And if you really need to give yourself a break. Just mark all the cards as “Hard” for the day without even reviewing them and start again the next day. You could also strategically mark some kanji “Again” if you think those in particular need to be attended to sooner. It’s all up to you. The SRS works for you, not the other way around.

Balance is everything.

As usual, How to Japanese is a call for mindfulness. Know thyself, student! What do you need for your studies? What works for you? I know I generally need some kind of structure, whether it’s the motivation of writing a review to propel me through a massive Murakami novel or letting myself watch J Drama/listen to Japanese radio while doing kanji study to get me through the next set for that day. I kind of knew I would need structure to get through the kanji in a way like this. Purchasing a manga monthly motivated me to take up regularly reading new artists and stories, and then that fell off in the spring as I binged Murakami in preparation for a podcast. But I also let my routines fall to the wayside if I’m unable to keep them going. I didn’t punish myself for enjoying Tears of the Kingdom.

And balance doesn’t have to be an all or nothing equation. I still listen to NHK Radio News, but I’ve only been listening to the hour-long ジャーナル (“journal”) episodes, not every episode possible as I was during the months of IUC remote study I did in Chicago.

What comes next for me? I’ve been letting myself enjoy some books in English, notably the new translations of Ao Omae and Akutagawa. I have a book of Japanese short essays I’m working through, and I want to find some new J Drama to watch. I want to do some writing in Japanese, but I haven’t quite had the energy for it. I’ll definitely be doing some writing in English. I’m hesitant to let my kanji practice go completely, but I don’t feel quite as bad as I did a couple months ago when I started to prioritize the Murakami novel and took my foot off the kanji gas. I’m easing back into a new focus, and we’ll see where that takes me.

One thing I will try to do more regularly is podcast. At this point, I’m only planning record an audio accompaniment to this newsletter. That feels like the most reasonable, balanced approach at the moment. But we’ll see where that takes us. If you haven’t already, please subscribe on your favorite podcast platform. I’m also going to experiment with adding it to each Substack newsletter. Let me know what you think!

Interesting! Do you have specific reasons for actively learning kanji, apart from 'making it stick more easily'? It's been a bit of a dream of mine to use Japanese more actively, maybe keep a small Ameblo or something, I just haven't been able to squeeze it in. I don't live in Japan so there's no immediate reward but even for those living in Japan, I wonder how useful it really is nowadays, being able to write kanji by hand?

I'm pretty happy with the rest of my post-N2 routine though: daily reps of 常用漢字 & vocabulary decks, reading & playing games when I feel like it plus the occasional online conversation lesson.