文壇

Exploring the literary world - How to Japanese - May 2024

This is How to Japanese, a monthly newsletter with something about Japan/Japanese and a dash of いろいろ.

日本・日本語: How to 文壇

Murakami Haruki has a short story titled 「夏帆」 (“Kaho”) in the June 2024 issue of 新潮 (Shinchō), which came out at the beginning of this month. It is extremely mid, as the kids say these days. The story starts on such a bizarre, almost misogynist note that I thought it was almost certainly irredeemable, but the last couple pages are more compellingly told. I’m not sure if they excuse the start or the overall premise: A woman is on a blind date, and the man says to her, “I’ve been on dates with a lot of women, but honestly, you’re the first ugly one.” (「これまでいろんな女性とデートのようなことをしたが」とその男は言った。「正直いって、君みたい醜い相手は初めてだ」)

Murakami wrote the story to read at an event on March 1 at Waseda with Kawakami Mieko, and her story is also included in the issue. (It’s much better.) The event is titled 春のみみずく朗読会 (The Owl Reads in Spring), which is a reference to Kawakami’s 2017 “long, long interview” with Murakami.

This makes me think that Murakami’s choice of topic was intentional. In the interview, which was translated in part over at Literary Hub in 2020, Kawakami criticizes Murakami’s depiction of women in his works: “…there’s a persistent tendency,” she says, “for women to be sacrificed for the sake of male leads.” “Kaho” feels like an attempt to show a female character standing up to a male antagonist.

I can’t recommend purchasing this issue of Shinchō for the Murakami story, but fortunately it has 600+ pages of other content to recommend it. In fact, this is the 120th anniversary edition and includes a virtual murderer’s row of 文壇 (bundan) writers.

The 文壇 is essentially the literary world in Japan. Using my sentence diagramming technique from last month’s newsletter, we can break down the first sentence of the Wikipedia entry like this: 文壇とは、X人たちのつながりと付き合いの世界のこと (Bundan to wa, X hitotachi no tsunagari to tsukiai no sekai no koto, The bundan is the world of connections and relations between people that are X).

What kind of people?

X = 作家、文芸評論家、雑誌編集長、出版社の編集者など文学・文筆活動を取り巻く (sakka, bungei hyōronka, zasshi henshūschō, shuppansha no henshūsha nado bungaku/bunpitsu katsudō wo torimaku, involved in literary/writing activities such as writers, literary critics, magazine editors, and editors at publishers).

(Here’s the Japanese sentence in full: 文壇とは、作家、文芸評論家、雑誌編集長、出版社の編集者など文学・文筆活動を取り巻く人たちのつながりと付き合いの世界のこと)

The 目次 (mokuji, index) of this issue almost cascades out of the magazine. I’m remembering fondly my article on indexes for the Japan Times. The index for this issue in particular is so highly regarded that the Shinchō website recreates the physical version online rather than just posting a digital list of the writers (as the June issue of 文藝春秋 [Bungeishunjū] does):

目次 really are the best way to get familiar with literature in Japan: Take 30 minutes every month, stop by a bookstore (or a website), and scan the index of every literary magazine in the store to see the names of the writers, what they are publishing/serializing, who is critiquing whom, who has won a prize, and who else got shortlisted. The more frequently you scan the names, the more familiar they will become.

The index here is six pages and in addition to Murakami and Kawakami, it includes stories from Yoshimoto Banana, EnJoe Toh, Machiya Ryōhei, Kanehara Hitomi, Kawakami Hiromi, and Yamada Amy amongst others (whom I’m just not familiar with but I’m sure are equally weighty in reputation).

However, I’d recommend skipping these writers for now and proceeding directly to the massive collection of 随筆 (zuihitsu, “miscellaneous writing”/essays) written especially for the issue under the theme 創作の小さな真実 (sōsaku no chīsa na shinjitsu, a small truth about creating). This section also includes a ton of big name writers! Murata Sayaka, Takahashi Gen’ichirō, Matayoshi Naoki, Ogawa Yōko, Ekuni Kaori, Yū Miri, and others. If you’re an advanced beginner or intermediate student, I feel like 随筆 is the kind of material that you will really benefit from reading.

First, 随筆 are short. Most of the essays are two pages each and give you the pleasure of finishing something you’ve read sooner than if you were reading a longer novel or novella. Even if you only read half a page a day, it will take you just four days to finish a complete work.

Second, the length and the fact that they are generally non-fiction encourages the economic storytelling of specific events. This gives students something to hold onto as they read. Fiction writers will often spend the first couple pages waxing poetic with intentionally difficult to decipher language. 随筆 writers do not have that luxury. They just get into it. I can recommend the Takahashi and Ogawa pieces in particular for these qualities. And if you’re looking for something slightly more abstract, check out the Ekuni essay after those.

The best thing about this issue in particular is that if you complete my 随筆 challenge, you’ll have read 34 different Japanese writers! You’ll have experienced a massive range of different writing styles, tones, subject matter, perspectives, figures of speech, and vocabulary. Perhaps one of these new writers will inspire you to read more, and more after that, eventually creating enough escape velocity to move beyond the gravity of Murakami Haruki so you can explore the farther reaches of the 文壇.

いろいろ

You may want to get your copy of Shinchō at a physical bookstore. Apparently it’s been selling out online. Check out the blog and podcast for details on other ways to pick up a copy.

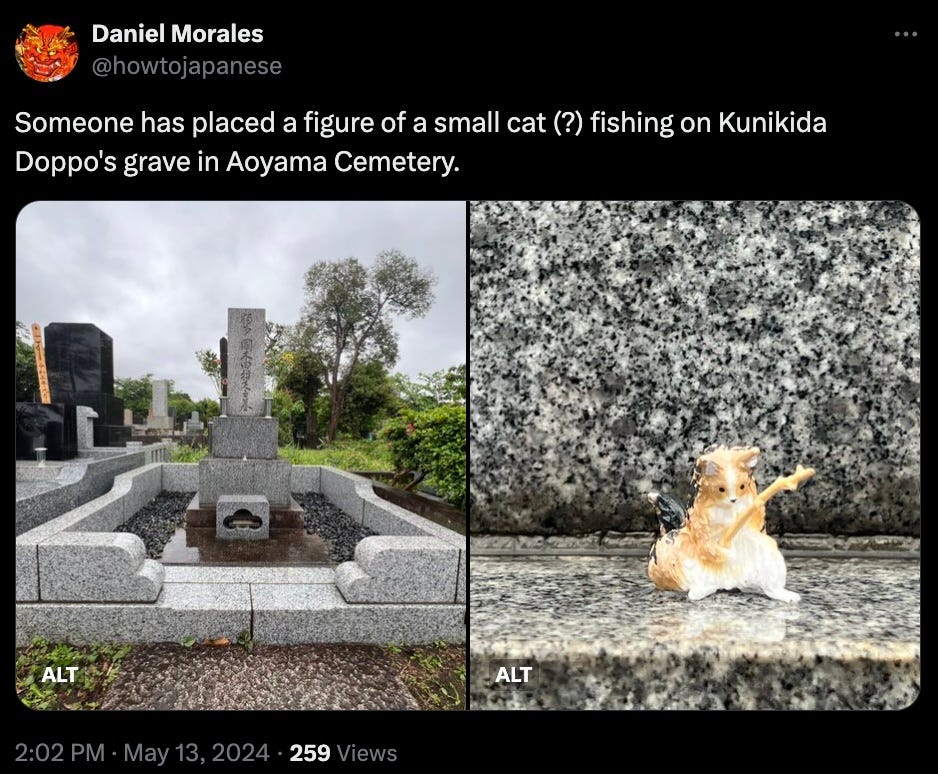

I was briefly in Tokyo last weekend, and when I found myself near Aoyama Cemetery, I droped by Kunikida Doppo’s grave. If you haven’t read 忘れえぬ人々 (Wasure’enu hitobito, Unforgettable People), it’s worth struggling through.

This YouGov report on global podcast listenership got a lot of attention amongst expats in Japan online because of how little Japanese listen to podcasts: “Only 10% of Japanese consumers listen to an hour of podcasts per week or more.” This seems especially strange given how much commuting the Japanese do. I’d be curious to know how much time they spend listening to music and how that compares to the rest of the world. Or maybe the survey was off? Maybe something (news broadcasts? comedy shows?) were not included as podcasts? I could see that being the case.

I had my first million-view tweet! It’s that genre of tweet that takes a popular Japanese tweet and translates it in a quote tweet, but I’m still thrilled. It’s the first time I’ve muted a conversation. Please clap.

A friend asked me about the survey and my first thought was that while Japanese spend a lot of time commuting, they don't tend to spend the time commuting by car. Since they're not driving, they have no reason to restrict themselves to audio-only material and so why listen to a podcast when you can watch YouTube scroll Twitter, scan Instagram, read manga or, if all else fails, browse the web.